The Science of Horse Racing: The Stride

(Photo by Coady Photography/Churchill Downs)

When humans walk, they simply put one foot in front the other but four-legged animals like horses have a few more options.

For a horse, the repeated pattern of natural leg movement, or stride, defines the gait while the horse’s body structure, or conformation, determines the efficiency of the gait. Watching a horse move around a paddock or a racetrack is a study in movement, from a simple walk, a faster trot, or a full-speed gallop, the coordination of their limbs fascinating in their efficiency. The study of how these thousand-pound animals move has inspired years of study, its debates making way for the pioneering work of one photographer which answered questions about what happens each time a hoof hits the ground.

Let’s look at the particulars of the stride and conformation and how horses move at each gait.

Stride

The unit of the gait is the stride which is the cycle of the movement of all four legs over a span called a stride length, with each hoof striking the ground at a particular time. When repeated, the stride defines the gait. For example, when a horse walks, his feet strike the ground in a different order than they would at higher speeds, such as a trot or gallop.

Strides have two phases: stance and suspension. Stance is when one or more of a horse’s feet are on the ground while suspension occurs when all four feet leave the ground. As the hoof strikes the ground and then pushes off, the amount of time it is on the ground, or breakover, determines the speed of the stride. The less time the front part of the hoof spends on the ground, the more quickly the horse will move forward. If they can propel themselves forward more efficiently, they will cover more ground in a shorter amount of time. Because horses have four feet, they spend more time striking the ground than suspended in air, but that suspension phase also determines the type of gait.

Different Gaits, Different Speeds

Horses have three basic natural gaits: walk, trot, and canter, with the gallop just a faster version of the latter. Each gait will have one or more feet touch the ground at different intervals depending on the horse’s speed, especially the gallop, where all four feet will be off the ground.

At a walk, the foot falls occur one at a time using a four-beat stride yielding a speed around 5 mph. The walking stance alternates using two or three feet on the ground and the horse bobs its head for increased balance. The trot, at around 10 mph, operates the legs in diagonal pairs forming a two-beat stride and is natural enough no additional head movement for balance is needed. This gait is the most efficient at slow speeds however the body of the horse will bob up and down causing less advanced riders to be jostled.

The canter is a three-beat stride and the gallop used in horse racing, where a horse can get up to or exceed 30 mph, is a faster four-beat stride. At a full speed gallop, the horse comes down first on its hind leg and then the diagonally opposite front leg and other hind leg, and lastly on the remaining front leg. As the horse prepares for the next stride, he is briefly suspended with all four feet off the ground before starting the sequence over again.

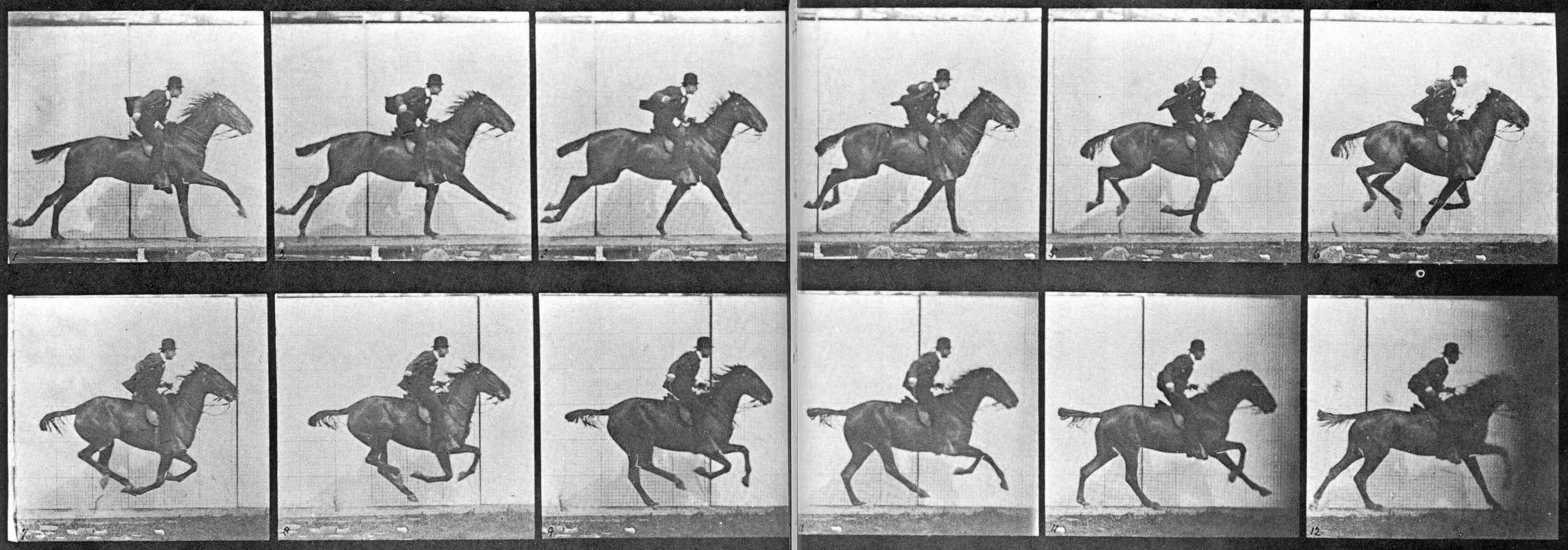

For years, observers were only able to guess at the pattern of the gallop because its speed made it difficult to ascertain the order the legs struck the ground. Assumptions about how the horse’s legs extend when galloping account for the depiction of all four legs extended during the suspension phase in paintings that predate the photographic era. However, Eadweard Muybridge’s landmark series of photographs from the 1870s captured a horse at full gallop, finally giving us a true look at the mechanics of a horse at its fastest gait and disproving the idea that horses extend all four legs outward when galloping.

For years, observers were only able to guess at the pattern of the gallop because its speed made it difficult to ascertain the order the legs struck the ground. Assumptions about how the horse’s legs extend when galloping account for the depiction of all four legs extended during the suspension phase in paintings that predate the photographic era. However, Eadweard Muybridge’s landmark series of photographs from the 1870s captured a horse at full gallop, finally giving us a true look at the mechanics of a horse at its fastest gait and disproving the idea that horses extend all four legs outward when galloping.

Muybridge horse gallop film (Photo courtesy of the Wikimedia Commons)

Conformation

Additionally, the length of a horse’s stride is a combination of their shoulder and hip conformation, or structure of the horse’s body. If a horse is shorter in the back, then the back legs will not meet the front legs. Conversely, horses that are longer in the back will overstep their front legs. We can see this in the foot fall patterns. Tracking where each hoof strikes the ground is one way to assess a horse’s shoulder and hip conformation. Great racehorses come in all sorts of packages, but ones like American Pharoah, noted for his smooth and balanced stride, tend to have the optimal shoulder and hip conformation for an efficient gait.

Another indicator of a horse’s potential speed is the angle of the front and hind legs at full extension. If you look at a photograph of Secretariat, for example, at full stride, the angles of his front and hind legs are 110°, an ideal form for a galloping horse. We know the length of both Secretariat’s and American Pharoah’s strides: while Secretariat’s stride was shorter than American Pharoah’s, 25 feet versus 26, that 110° gave Secretariat an advantage in how often his feet hit the ground.

In his 1973 Belmont Stakes victory, Secretariat ran his first quarter in :23 3/5, while American Pharoah’s time in 2015 was :24.06. For six furlongs, Secretariat ran 1:09 4/5 versus AP’s 1:13.41. Both ran their 1 1/4-mile times faster than their Derby performances by at least a half second, but American Pharoah’s final time for the 1 1/2 miles was 2:26.65 while Secretariat did it in 2:24, a record that still stands. Though American Pharoah’s stride was longer, Secretariat’s confirmation allowed him to propel himself forward at a faster rate. Because Secretariat’s breakover was more efficient, he was faster than American Pharoah despite their differences in stride length.

Next Time

From the order that their hooves strike the ground to the body structure that makes it all possible, understanding the science of racing is another tool for handicapping your next race day. You probably have heard analysts and handicappers discuss a horse’s ability to change leads during a race. How a racehorse handles changing that leading leg at full speed is an important part of predicting a racehorse’s performance on a given day. Next month’s Science of Racing will explore lead changes and how those affect a horse’ performance during a race.

ADVERTISEMENT