The Heart that Wears the Crown: Omaha

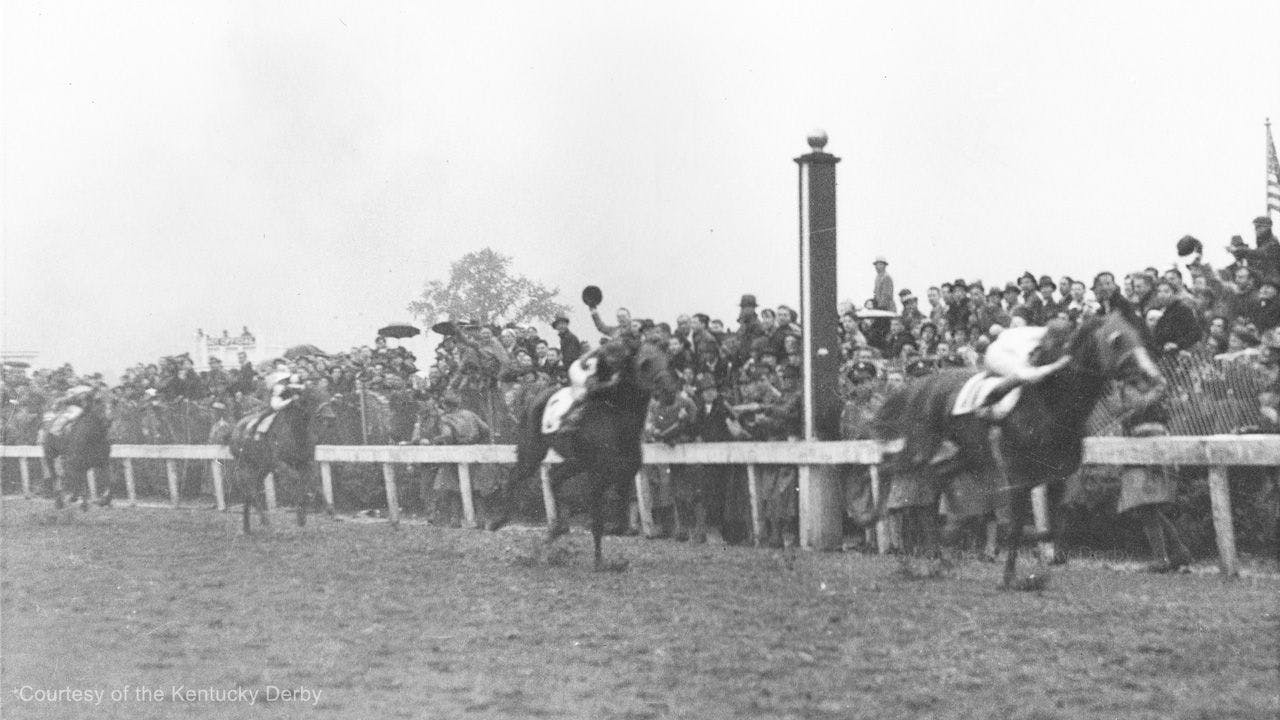

Omaha wins the 1935 Kentucky Derby (Courtesy of the Kentucky Derby/Churchill Downs)

Both Sir Barton and Gallant Fox showed what it took to win those first two Triple Crowns. Undaunted by distance and unaffected by the intervals between their contests, those champions rose to the occasion and showed what it meant to be great. They used their genetic gifts to win those classic races and earn a spot in the sport’s Hall of Fame, their examples the gold standard for others.

Omaha, the third horse to join this exclusive club, was one with a special connection to another member, sharing an owner, breeder, and trainer, yet forging his own path to the top.

Following the Fox

When any Triple Crown winner goes to stud, the high expectations set by winning that coveted trophy come along, as fans eagerly anticipate the next generation. Can he copy himself and produce another just like him? Of the 13 to have worn the crown, only one has done what is nearly impossible, a feat unlikely to be duplicated anytime soon: siring another Triple Crown winner.

In his first year at stud, Gallant Fox had a full book of mares, including William Woodward’s Flambino, who had finished third in the 1927 Belmont Stakes. From their pairing came a tall chestnut colt with a wide white blaze, Omaha. Named in honor of the Ormonde line from which he descended, the colt spent his early months at Claiborne Farm and then was sent to Belair Stud in Maryland as a weanling. There, Woodward, his English trainer Captain Cecil Boyd-Rochfort, and his American trainer “Sunny Jim” Fitzsimmons would sort the horses into those who would stay in the United States to race or be sold and those who would ship to England to Boyd-Rochfort’s Freemason Lodge.

Omaha before the Arlington Classic, his last start of 1935. "Sunny Jim" Fitzsimmons is on the left. I love photos like these; they make these names real & they show us how much racing has changed & remains the same many decades later. pic.twitter.com/NuejZCJnUS

— Jennifer Kelly (@foxesofbelair) January 21, 2021

Two yearlings, one by Sir Gallahad III and one by Gallant Fox, walked their paddocks while the men observed them, judging who would go where. The one by Gallant Fox would go to Fitzsimmons’ barn at Aqueduct, a yearling Omaha showing his trainer that he would likely be taller and more of a handful than his famed sire. Fitzsimmons remembered him as “the most excitable colt he ever trained,” according to Suzanne Wilding’s and Anthony Del Balso’s book on the Triple Crown winners. Luckily for Fitzsimmons, he had jockey Willie Saunders, a skilled rider from Montana, slated to ride the Belair colt in his three-year-old starts.

Saunders got to know Omaha well during those early months of 1935, discovering a secret about the tall Belair colt during a morning workout that spring. Fitzsimmons would work Omaha in company, sending out one or two others to exercise with the prized son of Gallant Fox. One of those companions brushed the colt, and, to Saunders’ surprise, Omaha grabbed a hold of his workmate. Afterward, the jockey convinced the other exercise rider to keep the incident under his hat. Other than trainer Fitzsimmons, no one else knew about the Belair colt’s propensity to bite.

To prevent Omaha from doing that during a race, Saunders would take the colt to the outside of the field, a natural position for a horse with such a long stride anyway. But it was not just to accommodate Omaha’s need for space to find his feet; no, it was about keeping the Triple Crown winner on his task and away from any competitors who might bump him into distraction. His strategy worked: Omaha went on to win the Triple Crown. Injury shortened the Belair star’s three-year-old season, though, preventing him from following the same path his sire Gallant Fox had traversed.

Instead, William Woodward decided to take a different tactic with his newest champion. Since Gallant Fox was standing stud already, the master of Belair instead sent the Triple Crown winner to England and the stable of trainer Boyd-Rochfort, where Omaha would prepare for the 1936 Ascot Gold Cup.

Omaha wins the 1935 Kentucky Derby. (Courtesy of the Kentucky Derby/Churchill Downs)

Forging His Own Path

Just getting off the Aquitania, the transatlantic liner that took him from New York to Southampton and his quest for Ascot glory, was an adventure. When the Captain’s men were loading the hot-headed colt onto a van that would take him to his next step, the flash of the photographers’ bulbs startled Omaha. He got loose from his handlers, running unshod down the docks. It would take sugar cubes to lure the colt back into the hands of the men sent there to pick him up, but he allowed them to catch him and safely transport him to Freemason Lodge.

As he settled in to his new stable, his groom Willie Stephenson noted that his new charge was a rather hot-headed individual. Stephenson worked to calm him down and ingratiate him into the Captain’s stable of high-quality horses. The nervous colt ate two rugs that had lined the floor of his stall, new additions to his accommodations that soon proved to be chew toys for the anxious horse. The Captain and his staff were good influences on the colt, who adjusted to racing on the grass and going the opposite direction with little trouble. After winning his first two races, both Woodward and Boyd-Rochfort were confident as the Ascot Gold Cup approached.

However, on Gold Cup day, the son of Gallant Fox was anxious and sweating before the big race. He nearly unseated jockey Pat Beasley in the post parade, but stood up valiantly to the challenge of the filly Quashed. The two battled down the Ascot stretch, neither giving an inch, the filly emerging victorious at the end. When Omaha met the starter again two weeks later, he was again an uneasy horse and needed six minutes and a very patient starter to contest the race. He finished a close second, a nice effort after his titanic struggle at Ascot, but the Captain saw that the colt would need more help to undo the pre-race nerves that he had developed.

If you could travel back in time to watch one race live, what would it be?

— World Horse Racing (@WHR) April 6, 2020

📸: QUASHED 🇬🇧 vs. OMAHA 🇺🇸 1936 Gold Cup @Ascot. pic.twitter.com/owZYBaNJCM

Boyd-Rochfort brought the Triple Crown winner to the paddock at Goodwood to school with the hopes that it would help to calm him before he raced again. But he was not slated to race that day, so he did not go to the post with the other horses, leaving Omaha looking almost forlorn when he stayed behind. After an injury ended his 1937 season before he could race again, the Belair champion was shipped back to the United States to stand stud, first at Claiborne Farm and then at the Jockey Club’s breeding farm in upstate New York. In 1950, Omaha went west to Nebraska, where he stayed for the rest of his life. There, he stood at Grove and Mort Porter’s farm near Nebraska City.

Those Final Years

In his final years, Omaha had mostly calmed down from that nervous horse who needed to be taken to the outside during his biggest races and acted out in the post parade before one of the world’s most famous races. Despite being years removed from the racetrack, the old man still showed the same fire whenever he was reminded of those days. On his annual trips to Ak-Sar-Ben Race Track, where he would parade before the Omaha Gold Cup, he would get excited at the sound of the starting gate, like he was ready to run leaving Porter with his hands full holding on to the stallion. It was a testament to the competitive drive that fuels Thoroughbreds to give all they can each time they race. Omaha did not lose that, even in his final days.

To wear the crown, a horse must show not just the speed and stamina necessary to win those three classic races in a short five weeks. He must have the heart to keep going even when confronted with the toughest of challenges, the drive to outlast his competition and continue pushing for that finish line. In a little over a century, only 13 have worn that immortal mantle, horses that possessed everything required to win a crown and a place in the sport’s long memory.

ADVERTISEMENT