The Science of Horse Racing: Colic and Laminitis

(Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

When Secretariat died in October 1989, the world mourned the passing of this Triple Crown winning and racing immortal. At the age of nineteen, it was not old age that took Big Red, but laminitis, a painful hoof ailment that does not discriminate, affecting both claimers and champions.

In 2001, Kentucky Derby winner and influential sire Unbridled underwent surgery for intestinal issues twice, but soon battled colic again despite that intervention. The stallion was eventually euthanized when it was clear that a full recovery was not possible, another example of its indiscriminate nature.

Both colic and laminitis come up as health issues that affect horses both on the racetrack and off.

Some horses recover and go on to return to racing while others are not so lucky. For the final Science of Horse Racing in 2022, let’s explore these conditions to better understand how both could become serious enough to take these two champions.

Secretariat wins the Preakness S. 1973 (Photo by Jim McCue/Maryland Jockey Club)

Laminitis

Earlier this year, The Science of Horse Racing looked at the structure of a horse’s hoof, including the bones inside each. In all four, a horse has a pedal bone, also called the coffin bone, which is the internal skeletal structure of the foot. Surrounding this bone is the corium, which provides nutrition to the hoof and bonds the fingernail-like outer shell to the pedal bone; this bond prevents that bone from penetrating the sole of the foot. The tissue that bonds the hoof wall to the pedal bone are called lamellae.

Unbridled (Courtesy of Churchill Downs/Kentucky Derby)

To withstand the force of the foot at a gallop and allow the hoof to grow continuously, these lamellae are comprised of hundreds of folds of tissue with both ample blood supply and nerve connections. Each hoof contains at least 600 primary lamellae, and each of those have another 100 secondary lamellae within, providing enough surface area to keep the hoof wall connected to the pedal bone. When these structures are compromised, they cannot maintain the blood supply necessary to keep the hoof healthy and the pedal bone in place. As the hoof wall starts to separate, it crushes the structures of the foot underneath, causing pain. This is called laminitis.

The causes of laminitis can vary, ranging from a high fever or other illness to changes in weight bearing. Any sort of illness that involves a fever can cause disruptions in a horse’s metabolism, which can affect how nutrients are distributed through the body. Shifts in how a horse carries their weight, such as stepping on a nail and injuring a hoof, can put too much pressure on the lamellae in the other feet, which in turn leads to laminitis. Other triggers include sepsis, colic, and poor hoof care, all of which can contribute to this condition.

Signs of laminitis can be subtle at first. Lameness is often the initial hint that something is amiss. Next, a horse may shift their weight from foot to foot. They might be reluctant to turn or show changes in their behavior or personality. A change in stride or a stiff gait may also be signs of pain and discomfort. Eventually the hoof becomes mishapen and visible changes in the coloration of the hoof also can develop. These changes are a result of the lamellae separating from the hoof and the blood flow to the outer hoof wall being disrupted.

Treatment for laminitis generally depends on its cause. Fluids can help if a horse is dehydrated because of a fever or other illness. Encouraging the animal to lay down more and stabling them with soft bedding can take pressure off the affected feet. Treating any abscesses that might develop can help with discomfort as can special shoes and corrective trimming from the farrier.

It is possible for a horse to recover from laminitis and resume their normal activities. Lady Eli stepped on a nail during her three-year-old season, which led to laminitis in both of her front feet. Immediate treatment enabled her to return to racing the following year. Sometimes, no matter how much care a horse gets, laminitis causes severe and irreparable damage to a horse’s hooves, leaving them in constant pain. When that happens, in the case of both Secretariat and Barbaro, the most humane course of action is euthanasia.

Sometimes, despite all of the possible treatment and their will to live, battling laminitis can be too much for even the greatest of horses. Colic can elicit the same kind of toll on any horse.

Colic

You might hear the term colic and think of the connection with young babies and the period of crying that comes with potential digestive sensitivities or other triggers. For horses, though, colic is a more generic term that refers to any sort of pain or discomfort with the abdomen. How their digestive systems have evolved is behind many of the issues that cause colic.

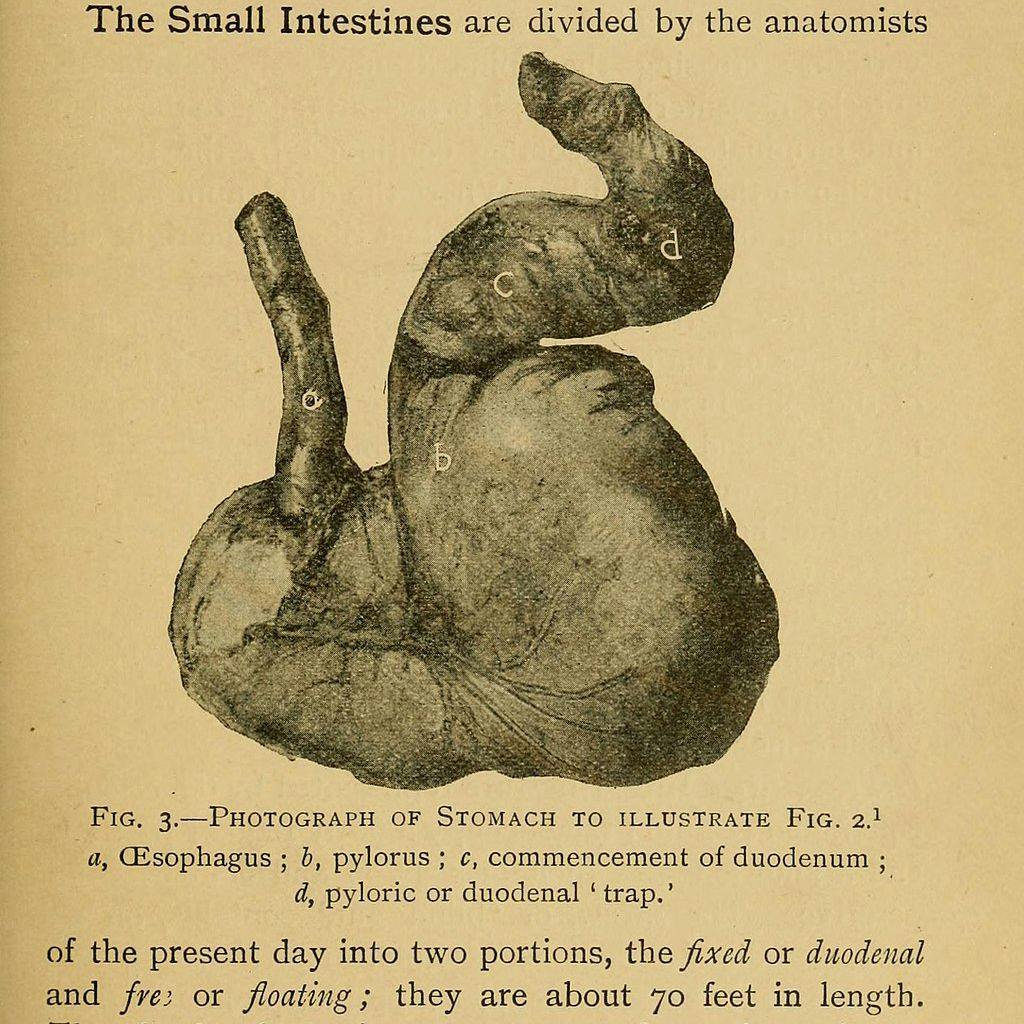

Horse Abdomen Map (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/H. Caulton Reeks)

Horses are natural foragers, eating mainly grass and hay in small amounts. In general, they also are unable to vomit, so, if they eat bad feed or overindulge, they cannot empty their stomachs as we might. Their esophageal sphincter, the valve that allows food to go from the stomach to the intestines, is a one-way street for the most part, which moves everything relatively quickly through a horse’s digestive system. These can cause blockages in the intestines, which then leads to discomfort and pain and quickly can be emergency situations.

Because colic has different causes, it also comes in more than one form. The most basic is gas colic, generally caused by stress or limited opportunities to forage. Obstructions in the gastrointestinal system can cause colic as well, producing a blockage which can cause the intestines to twist when spasms cannot move the food along the digestive tract. Colic can also be functional, where inflammation prevents a horse’s body from working as it should. All of these can become serious rapidly, so early intervention is key to helping a horse deal with colic.

Early signs include a horse looking at their abdomen, lying down or rolling, passing less manure, and changes in eating and drinking. Once a veterinarian is on hand to observe the colicking horse, they can determine the type of colic and then the treatments that can help. They might insert a tube through the nose, down the esophagus, and into the stomach to run mineral oil and water to rehydrate and prompt the gut to start moving again. Once the blockage is removed, additional fluids can help relieve the discomfort that comes with colic.

Depending on the seriousness of each case, additional treatments might include surgery if a blockage cannot resolve on its own or if scar tissue prevents a horse’s gastrointestinal system from working properly. The very worst cases of colic can result in euthanasia if the horse’s digestive system has been damaged enough to compromise digestion. Sir Barton, America’s first Triple Crown winner, suffered from several attacks of colic in late 1937, eventually succumbing to the damage it caused. Both Shared Belief and Roaring Lion are among the notable horses who had to be euthanized after bouts with colic.

Horse Stomach (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/H. Caulton Reeks)

Final Thoughts

Laminitis and colic are just two of the ailments that can affect horses of all breeds, from Thoroughbreds to Clydesdales and beyond. Both are serious enough that they can take the hardiest of horses like Secretariat and Roaring Lion so exploring each gives perspective about how such champions can be felled by these conditions.

Over the course of 2022, the Science of Horse Racing has looked at everything from the stride to coat colors to jockey stances, sharing the facts behind each and adding to our understanding of why we see more bay horses than gray and what makes that crouch the preferred seat for race riders. Understanding these topics like the makeup of a horse’s hoof and the mechanics of the stride can give you that much more information about these wonderful animals as you look forward to another day at the races.

ADVERTISEMENT