The Science of Horse Racing: Four Legs and Infinite Questions

Horses are animals of contradictions. Though they can weigh more than a thousand pounds, they are technically prey animals, pursued by hunters like mountain lions and wolves. They are agile and fast but run on bones that are comparable to those of the humans that work with them.

Injuries to a horse’s leg bones can mean a range of outcomes, requiring everything from simply time to heal to ultimately having to let go of a beloved companion. From Spanish Riddle to Epicenter, the reality of the legs’ structures makes treatment and recovery a tenuous and difficult outcome that is dependent on a number of variables.

Anatomy of an Athlete

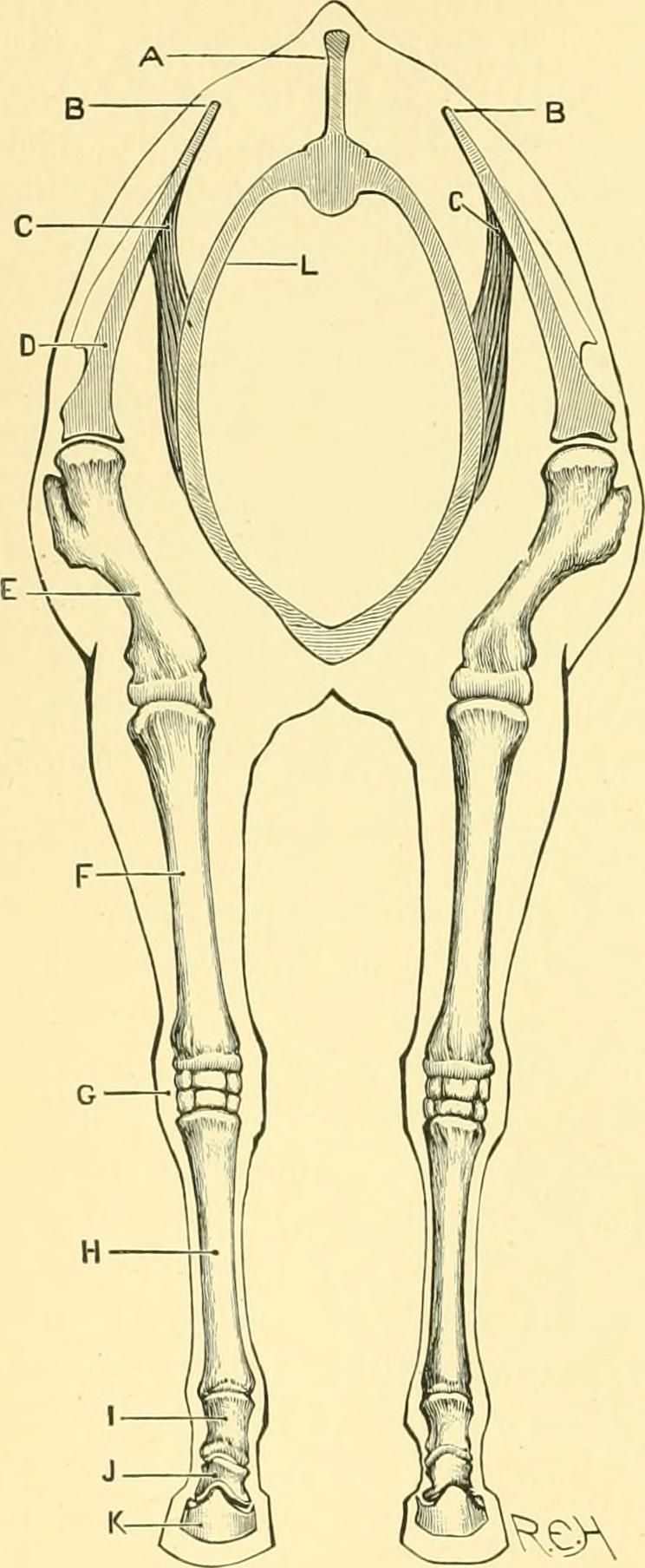

As quadrupeds, horses have four legs, two forelegs and two hindlegs. The structure of each pair differs from the top to the knee, where the lower leg begins; below the knee, all four are structured the same way, which starts with the cannon bone, the splint bones, the sesamoid bones, the long and short pastern bones, and the coffin and the distal sesamoid bones, which are contained within the hoof.

Because horses do not have collarbones as humans do, their forelegs are not connected to their spines, but instead are connected to their torsos via muscles and tendons. This structure allows the horse to completely fold up his legs when jumping, enabling them to clear taller obstacles. Additionally, the forelegs absorb most of the horse’s weight, which contributes to higher rates of injury in that area of the body than in the hind legs. The foreleg starts with the scapula, or the shoulder blade; the humerus; the radius; the ulna; the shoulder joint; the elbow joint; and the carpus, or the knee.

While the hindlegs absorb only about 40% of a horse’s weight, they also provide much of the propulsion. These are connected to the horse’s spine via the pelvis, which is wider in fillies and mares than it is in male horses. From there, the hind leg is comprised of the femur, the patella, the tibia, the fibula, the hip joint, the stifle joint, and the tarsus, also known as the hock.

The way that a horse’s legs are put together can give you a hint as to the advantages and disadvantages of their individual conformation, or the way their physiques are put together. Through hundreds of years of breeding and racing Thoroughbreds, ideas about what constitutes the ideal conformation of a horse for a particular surface or distance help those involved in the sport assess the horses they might be considering for their next racing prospect.

#FridayFact: There are no bones that connect a horse’s front legs to the rest of their body. Since horses do not have a “collar bone” like humans do, the forelimbs are only attached to the body by muscles and fascia underneath the shoulder blade (scapula). pic.twitter.com/smIoONnQMq

— FLAIR Strips (@FLAIRstrips) April 7, 2023

What Can Happen

Understanding how a horse is built can not only help a bloodstock agent assess the potential of a yearling but also help a veterinarian evaluate any potential issues a horse may encounter during their careers. Additionally, this basic overview of the structures of the front and hind legs leads next to a discussion of the common injuries. Bone bruises, popped splints, and fractures are among the most common skeletal issues in Thoroughbreds.

Bone bruises happen when the subchondral bone, the layer beneath the cartilage in a horse’s weight-bearing joints, endures repeated trauma from training or racing at high speeds, for example. If left untreated, such damage can lead to more serious injuries so early diagnosis is key. If a horse shows signs of lameness or soreness that does not appear to involve muscles and tendons in that area, then an x-ray can look at the skeletal structures to see if those are involved. Once a veterinarian diagnoses bone bruising, then anti-inflammatories like aspirin can help increase blood flow to the area to start the recovery process. From there, activities like swimming, which does not put continued stress on the bruised area, can help keep a horse active while still enabling the bone to heal.

Another common injury, especially in younger horses, is popped splints. Splints are bony growths on the metatarsal or metacarpal bones, located on either side of the cannon bones in a horse’s lower legs. Popped splints tend to happen because of repeated concussion to those areas of the leg and poor conformation of the lower leg. These can cause lameness, but some horses do pop splints without any indication of soreness. To treat this condition, veterinarians can use hot/cold therapies, supportive wraps, and rest. Chronic issues with splints can also lead to bony growths, which can cause repeated muscle soreness. In that case, surgery might be required to trim down those growths to prevent more serious issues.

Of course, bone fractures are the most serious skeletal injuries. While humans can generally have a cast to keep the bone in place and try not to put weight on the bone while a fracture heals, horses cannot do that. Since horses must be able to stand on all four legs, it is rare that they can use a sling or other intervention to help with healing from a fracture. Hence, the nature of the break can determine the right treatment.

Because a horse puts so much force on his legs and because a horse’s legs are comprised mostly of skin, bone, tendon, and nerves below a certain point, fractures are exceedingly challenging to treat. That force he exerts on that bone while running can change a simple fracture into a shattered bone if he cannot be immediately immobilized. That is why you will see riders do everything they can to pull up a horse once they detect a problem. Treatment is far more likely to be successful if the intervention is swift.

Additionally, horses are prey animals and are continuously on the move so keeping them still long enough to intervene or repair a fracture is extremely difficult. Lastly, horses must be able to put weight on all of their limbs or else they can develop laminitis, a painful condition that affects the laminae in the hoof. Once laminitis sets in, causing pain in all limbs, often the most humane intervention is euthanasia.

Racing has made strides throughout the last few decades to cut down on such catastrophic injuries and offer horses the best chance to recover from injuries. Those efforts continue as both science and technology combine in an effort to do everything humanly possible for these wonderful athletes and companions.

Learning For Next Time

From Ruffian to Go for Wand, Hoist the Flag to Spanish Riddle, the story of the sport has plenty of examples of the tragedy and triumphs that come with the four legs that propel these horses into our hearts. Sometimes, fortune is on our side and we can treat a fracture so that a horse like Epicenter or Hoist the Flag can go on to the next phase of their careers. Other times, we come together to mourn when fortune does not smile on us but gives us a chance to learn so that, maybe next time, the outcome is more positive.

Understanding how a horse is built gives us the knowledge we need to appreciate the intricacies of our four-legged friends and companions and do the best we can for them when they need us.

ADVERTISEMENT